Other priorities

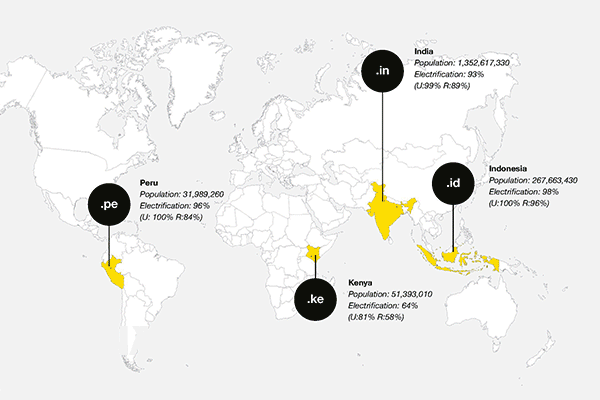

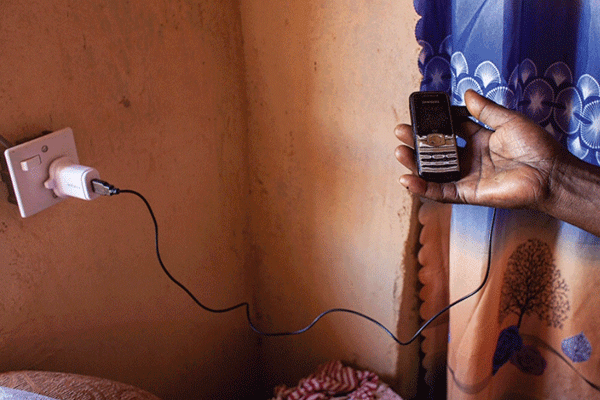

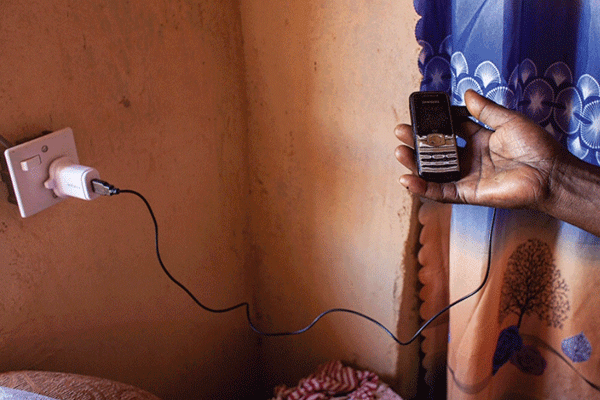

Many of the households visited within the reach of the grid that did not have electricity were simply unable to afford it. Needs like building stronger homes, affording their children's education fees, or buying food to put on the table often had to be prioritized. That being said, many homes without any electricity had cellphones which they'd charge at a neighbor's home or send into the city when someone was going to the market and pay to charge it at a shop.

Households without electricity often had feature phones which they'd charge at their neighbors' or in the closest city.

Costly habits

Energy needs in low-income households were often met with less sustainable alternatives like firewood for cooking and batteries for electronics like radios. Firewood was appealing because it was freely available to most households and batteries offered easy opt-in and opt-out solutions even if expensive. Oil lamps remained trusted backups as they were easy to fix or assemble from scratch.

Energy comes from many other sources like combustibles or batteries.

Key Needs

For those who were able to afford access to energy, either in a limited fashion through home solar products (picoPV or SHSs) or grid connections, the first devices invested in (varies across geographies and the quality of electrification) were bulbs, fans, and TVs.

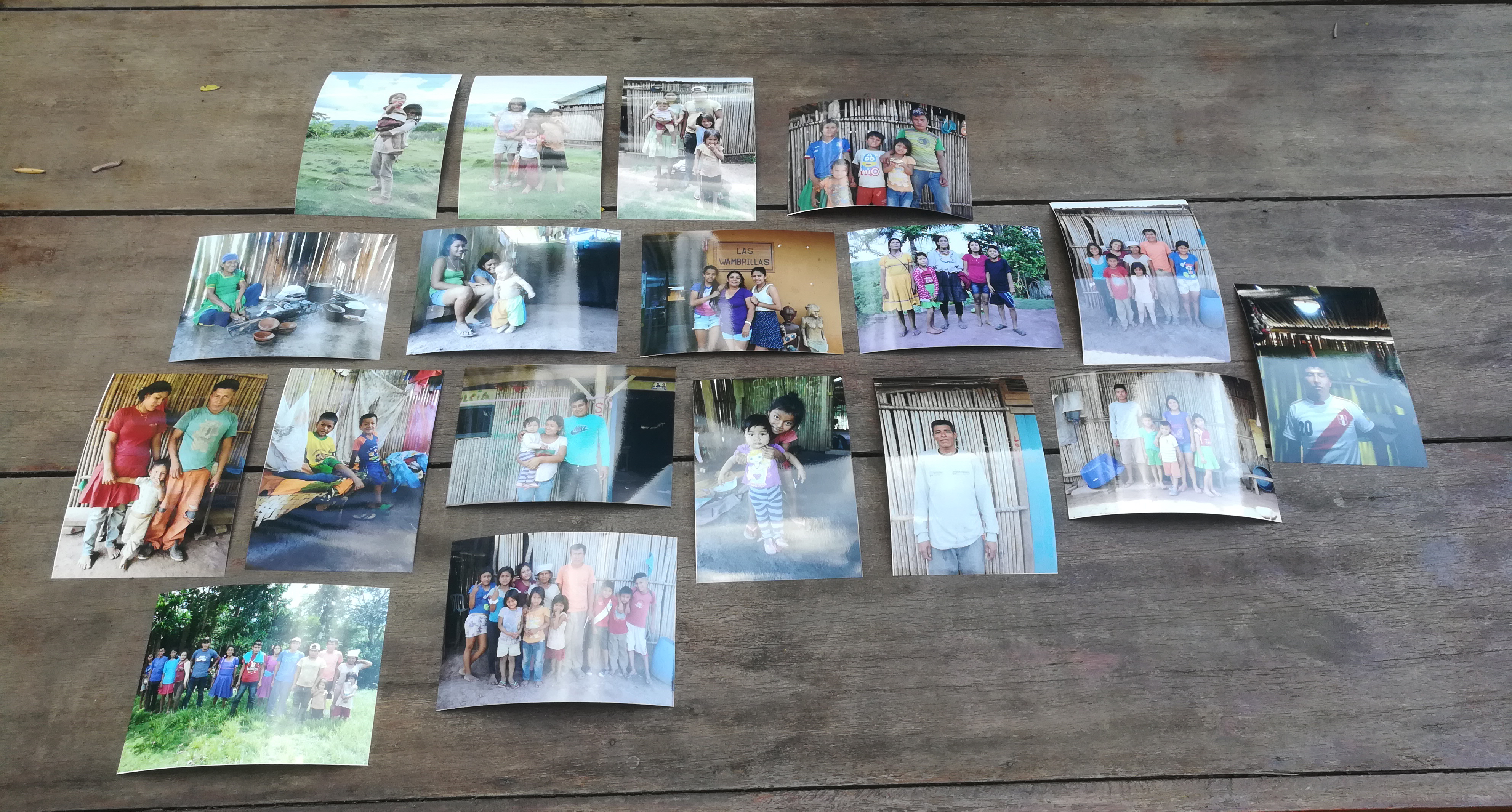

Light can extend active (or productive) hours: women in Peru mentioned using lights to weave at night as a way of relaxing and making a little extra cash. Many of these areas being tropical or sub-tropical fans and cooling devices was a big concern as well.

Lastly, the TV became a key sign of the quality of the electrification: it is a very appealing product but the home needs enough capacity to run a TV and if the connection is inconsistent the TV might fry and become too expensive to repair. We saw many more TVs in Kenya and Indonesia than anywhere else.

The availabilty and use of TVs became an interesting indicator of the quality of the energy access.

The Solar Trade-off

All in all we found solar can work as a temporary solution (even if temporary means decades), and greatly impact households' lives by providing affordable access to electricity, reducing exposure to toxins, and increasing productive hours. It might even be chosen over a grid connection in areas where the grid is so poorly installed that it puts children or cattle at risk and because it can run during storms without shutting down.

However, its ability to provide a lifestyle that is desired, a lifestyle "like in the city" (a phrase that came up many times), solar's capacity remains far too limited as of now. Even communities with solar mini-grids, as seen in Indonesia, struggle to meet the needs of multiple households especially during peak hours when families are relaxing in front of the TV.

Solar is a promising, reliable and adaptable source of energy but needs further innovation to become relevant in the long term.